The Legacy of Alice Betteridge

Alice Betteridge changed they way Deafblind children were seen in Australia and made sure everyone could see their potential rather than a disability.

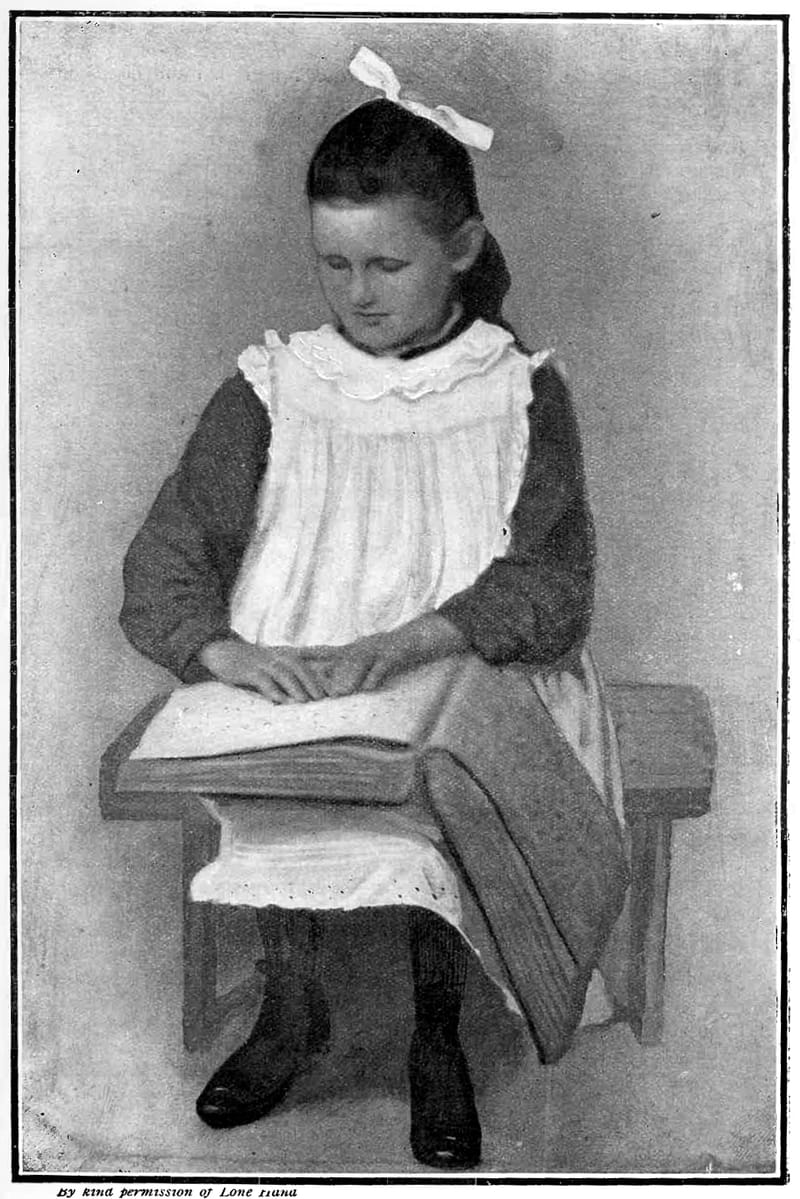

Alice Mary Betteridge Chapman (14 February 1901 – 1 September 1966) was an Australian woman known as the first deafblind child to be educated in the country.

Born in the Hunter Region at Sawyers Gully, near Maitland, New South Wales to parents George and Emily, Betteridge became blind at the age of two from suspected meningitis. Her mother took her to the Institution for Deaf and Dumb and Blind in 1904, but she was thought to be too young, and was sent home after a few months. She returned to the school in 1908, aged 7, to begin her education as the school's first deafblind student.

In a story that echoes that of Helen Keller, Betteridge's teacher Roberta Reid fingerspelled words into her pupil's hand, until Betteridge made the connection between the words spelled and the objects she was touching. The breakthrough came when Reid spelled the word "shoe" while placing a shoe in Alice's hand. Her education then progressed rapidly, and in a few short months she knew 200 nouns and several verbs, including "run," "jump," and "laugh," and soon began learning to read braille. In 1920 when she graduated, she was dux of the school. After graduating she remained at the school as a teacher for 9 years, before leaving Darlinghurst and returning to the family farm in Denman.

In 1939, Betteridge married Will Chapman (also deafblind), with whom she had been corresponding by mail for some time, and moved to live with him in Melbourne. They were married for nine years before he died of a heart attack in 1948. Betteridge returned to Sydney, and was well regarded for her intelligence, good nature and her independence, even travelling overseas. She died from cancer aged 65.

Betteridge meeting Helen Keller

The Alice Betteridge School at the RIDBC for students with a sensory and intellectual disability is named in her honour. Today, the RIDBC Alice Betteridge School educates 21 students who are deafblind or have vision loss, as well as a level of intellectual impairment.

Perhaps her greatest legacy is that she reminds us all that her, like all children, have the potential when the are nurtured, educated and loved the way they need to be.